Unique challenges in scaling AI-driven HVAC control

Introduction

The building stock is vast: in the US, there are more than 5.6 million commercial buildings (as of 2018), and in Europe (UK included), the number of non-residential buildings is around 12 million. This represents a huge potential for energy savings, as buildings are responsible for a large part of the energy consumption in these regions. One of the largest consumers of energy in buildings is the Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning (HVAC) system, which can account for up to 60% of the total energy consumption of a building. That’s why many actors in the building industry are looking at solutions to optimize the control of these systems, whether it’s to reduce energy consumption (energy savings-driven), power demand (cost savings-driven), while maintaining or improving the comfort of the occupants.

However, each building is unique (hence the “snowflake” metaphor). Research has shown that available optimization techniques are not easily transferable from one building to another, and that the engineering effort required to adapt a solution to a new building is significant.

In this article, we’ll focus precisely on this matter: the challenges of scaling AI-driven HVAC control optimization solutions, or what is missing to make these solutions easily deployable in a large number of buildings. We’ll attempt to open perspectives on how to tackle these challenges, while most of them are still open questions.

Scalability in the context of building control optimization

Designing a control optimization solution requires considering two main efforts: modeling the system dynamics and training an optimal control policy. Whether we’re talking about Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) or Model Predictive Control (MPC), these two efforts exist, although their respective intensity in terms of engineering effort may vary depending on the modeling approach (white-box, grey-box, black-box), and the technique used to train the control policy.

The scalability of the solution will then depend on its ability to reduce the engineering effort required to model the system dynamics and to train a control policy. It will also be measured by the engineering effort to transfer an existing set of models and policies to a new environment, and to adapt them to this new environment.

Let’s first bring a definition of the measure of “scalability”: it could be summarized by the number of distinct real-world control environments that can be handled by a certain number of “units of work”, provided by engineering time. We’ll assume first that engineering time is mostly spent on system dynamics modeling and policy training (although deployment, integration and maintenance are also important parts of the engineering effort).

The table below gives two arbitrary examples of unscalable and scalable solutions. Numbers give an order of magnitude of the engineering effort required to handle a certain number of environments, and what we should aim for.

A first angle to approach the problem is by defining how scalability of the solution is impacted by the complexity of a project. Intuitively, the larger the control perimeter, the more complex it gets, and the less likely it is that we’d be able to apply a generic solution to it. For instance, controlling a large building with many different systems and usages with a single policy seems to require a custom solution. On the other end, a zone-level controller may be easier to design for reusability.

In above graph, the red-dotted line represents the limit of the complexity of a project that can be handled by a generic solution. It’s placed quite arbitrarily, but experimental evidence shows that a single air or water loop controller is already a challenge to design for reusability. Red and green boxes are here to remind us what we could achieve at each end of the spectrum, “off-the-shelf” product pointing to a very generic solution, that doesn’t require significant effort for deployment, hence ensuring scalability.

Another dimension to the problem is the generalization and adaptability of the modeling techniques we use to create the control policy. For instance, we know now that the larger the number of parameters of a neural network, the better its ability to generalize (a recent example is Large Language Model - LLM). Another way to design the solution for better scalability is to split the control problem into smaller sub-problems, each with its own control and modeling requirements, and then to select the appropriate controller at deployment time. This is the idea behind agents pooling or agents library, that may be specialized by task, by type of environment, or by system. In both cases, dataset size is also a key factor. The larger the number of parameters of the model, the larger the dataset needed to train it.

System dynamics modeling is also part of the equation, with scalability ranging from 0 with custom white-box models to 1 if we can acquire one or more generic models that can be re-parameterized for a new environment with minimal engineering effort or if offline RL can be used to learn a model from collected data.

For now, we’ve seen scalability from the perspective of the control optimization problem only, and it could be seen as a synonym of “generalization capability”, or “transferability”, which are known challenges specific to AI-driven solutions.

However, here, the scalability will also depend on the connectivity and interoperability of the Building Management System (BMS). This won’t be the focus of this article, but it’s worth mentioning that deployment time in a building energy optimization project can account for up to 50% of the total project time and cost, given the heterogeneity of systems, internal and external communication protocols, and globally the lack of standardization. Even if efforts are made towards this direction (BACnet for communication, Bricks / Haystack / ASHRAE 223P for metadata), the problem won’t be solved in the near future, as old buildings won’t be upgraded overnight.

In above diagram, we see steps that can be taken to reach a “scalable BMS solution” from the extreme of a building not yet equipped with a BMS - which actually represents the largest part of the building stock (small buildings). For people familiar with BMS and integration, this looks like a lifetime challenge. Applying this reasoning, building by building, doesn’t seem doable in a reasonable time frame, not to mention the cost.

Moving towards data-driven solutions

If we want to achieve scalability, adopting data-driven techniques seems natural. Indeed, white-box or even grey-box models require a lot of engineering effort to be adapted to a new environment, and constructing then maintaining a library of detailed models for a large number of environments is not tractable. Similarly, training policies online in a simulator is not scalable, due to the engineering and computing resources needed. Doing it online in the real world isn’t scalable either, due to the sample inefficiency of available RL techniques and the nature of the controlled system (risks of discomfort, hardware failures, etc.).

But as we’ll see now, despite the appeal of going purely data-driven, the road is paved with challenges.

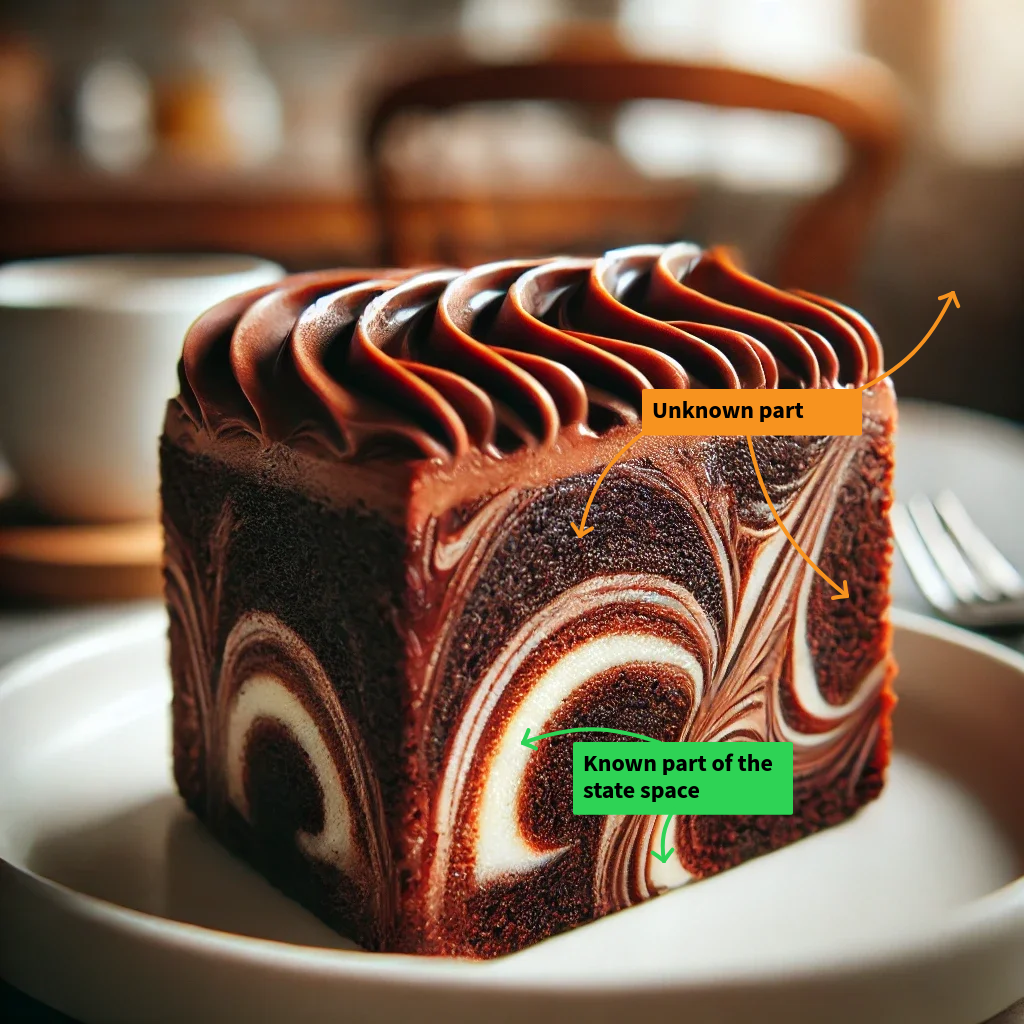

The marble cake dilemma

We often refer to the problem of limited data for crafting predictive models by using the metaphor of the “fog of war”: the collected data gives satisfactory information about the “central” parts of a distribution, but the further we go from the “center”, the less information we have.

However, in industrial control, and typically in HVAC control, the problem is more akin to “the marble cake dilemma”: most parts of the cake (chocolate) and surroundings are unknown, other parts (very few) are known.

Why? Because the system dynamics (state space, transition function) is not a single, continuous distribution, but a mixture of different distributions, each corresponding to a different operating mode of the system, under specific conditions (occupancy, weather). Moreover, the collected data is likely to reflect only steady-state conditions, and not the transient dynamics of the system, which are crucial for control. In addition to that, classic controllers aren’t meant to explore the state space, so there is a good chance that large parts of the state space and the transition dynamics are unexplored.

More theoretically, we can state the problem as an offline RL problem, where we would want to learn a policy under system dynamics that are partially known. The actual dynamics or transition function could be expressed as follows:

$$ \begin{equation} p(s'_t | a_t, s_t) = \begin{cases} p_{known}(s'_t | a_t, s_t) & [s,a] \in \mathcal{D_{known}} \\ p_{unknown}(s'_t | a_t, s_t) & [s,a] \in \mathcal{D_{unknown}} \end{cases} \end{equation} $$

Not being able to identify the unknown system dynamics would severely impact the response of the model when prompted on out-of-support regions, which can lead to catastrophic failures in control.

How to deal with this problem when we need to build a predictive model of the system dynamics?

One way to mitigate this issue is to use a model that can provide uncertainty estimates, and to use these estimates to decide whether to trust the model or not. We also have probabilistic tools like bayesian optimization, or the use of a model ensemble, than can better capture the uncertainty of the model. However, these approaches are not always applicable in the context of HVAC control, where the system dynamics are complex.

Hybrid approaches could also be employed, where a white-box or grey-box model with reduced order of complexity is used to complement the data-driven model. But this brings us one step back in terms of scalability.

Although no single answer exists to this problem, we can think of a few directions to explore and principles to follow:

- there is never enough data. A data-driven approach must account for this and aim for data collection strategies that maximize the amount and quality of the data. In practice, that would mean the first step in a project would be to deploy sensors and data loggers to collect as much data as possible. Inventory of historical data should also be done, and data augmentation techniques should be used to increase the amount of data available for training. Continuous data collection for model retraining will be key too.

- the model should be able to provide uncertainty estimates.

- complementing the data-driven model with generic white or grey-box models, that can help the policy learn strategies backed by physics.

Characterizing the execution context

We said already that buildings are snowflakes, and that the state space we provide as input to a control policy can be a complex mixture of different distributions.

Transition dynamics of the system in two different buildings will produce different trajectories in the state space, given the same set of actions. In the following graph, we see that the same action applied to two different systems governed by different transition dynamics will lead to two different trajectories in the state space.

The reason is simple: for the control policy to be effective, we can’t only provide sensor data like temperature, humidity, etc. We need to provide the policy with a context, from which it can infer the “static” properties of the building. This context must inform about the building envelope properties (conductivity, inertia), the HVAC system capabilities, etc.

When a policy is trained for a task in a specific building (online or offline), this context is implicitly provided in the training data. The policy infers the context through its interactions with the environment or by learning from a replay buffer, thus avoiding the need to explicitly provide it.

However, when we want to deploy the policy in a new building, we need to provide this context explicitly. This is particularly tricky given the number of possible combinations of “static” properties, and the fact that this context is not always directly available.

Can we employ existing techniques to perform system identification and contextualization of the policy execution? Domain randomization, state augmentation, uncertainty estimation, aren’t truly satisfactory. For instance state augmentation seems intractable given the number of possible combinations of building properties. A multi-modal input could be used, like mixing sensor data with a static definition (layout, conductivity, equipment power, …) but it requires upstream meta-data specification for each execution context, which may significantly degrade scalability.

Studies have been made also on transfer learning, where a policy is pre-trained on an environment, then fine-tuned on the target environment. How much can we transfer from one environment to another? We lack real-world examples of successful experiments. Also, zero-shot or few-shot fine-tuning is what we should aim for to minimize the risk of discomfort or hardware failures. However, the order of magnitude of the number of samples required to fine-tune, in a real world environment, is still an open question.

Online system identification is also at the center of recent research, as in “Offline Model-based Adaptable Policy Learning” (Chen et al., 2021), in which authors propose an offline RL method which performs identification by probing the system to select a suitable policy at deployment time. This is a promising approach, but performed in fully observable and deterministic environments (MuJoCo), and by prompting online, thus its transferability to building control is uncertain.

To summarize, and to give a more general definition of the problem, we could state that:

- a large part of the system dynamics will greatly vary and will be unknown in the target environment. The partial observability nature of the system will make it even more difficult to identify.

- pure offline system identification may not be scalable, given the number of possible combinations of building properties.

- online system identification is possible only if few shot learning is possible.

- hybrid and model-based approaches seem to be the most promising, but they will require a significant research and engineering effort.

Evaluating a control policy trained offline

For critical systems like HVAC, we need to build trust in the control policy before deploying it. This is particularly true for data-driven policies, which are often seen as black-boxes, and can’t offer strong guarantees on their behavior.

Since the true performance of the trained policy will only be known when it’s deployed in the real world, we need to rely on estimates. Many approaches exist, let’s cite a few:

- baseline comparison: the policy is compared to a baseline policy, like a PID controller, or a rule-based controller, in a generic, simulated environment. This is a simple and quite scalable approach, but it doesn’t provide strong guarantees on the performance of the policy. To improve on that, benchmarking can be seen as a way to mitigate uncertainty, as the policy is evaluated on a set of benchmark environments, that are representative of the environments where the policy will be deployed. This is a scalable approach, but it may require a significant initial effort to build the benchmark environments. In HVAC control, we particularly lack reference benchmarks, with standard environments and tasks to evaluate the performance of a policy.

- off-policy evaluation (OPE): the policy is evaluated on a dataset of collected data, generated by a different policy. This is particularly useful when the policy can’t be evaluated online, and it’s a scalable approach. It isn’t a widely adopted technique, but it’s backed by scientific research. At Foobot, we’ve started to work on that and open-sourced a tool in that direction, called Hopes. Below diagram shows the principle of OPE.

Note that these estimates, which are not based on a comparison with an accurate model of the system, are more subject to bias than, for instance, estimates based on reference white-box models. Designing a scalable evaluation framework for a control policy is a challenge in itself, and could be of great value for the industry.

Conclusion

Why seeking for scalability? Buildings represent one of the largest sources of energy consumption (40% of total energy consumed in the US and in Europe), and HVAC systems are responsible for a large part of this consumption (a 40%-60% range will sound familiar to many building owners). If we’re only able to optimize a small fraction of these systems, the impact will be too limited.

Whether it’s used to build predictors for model-based control or to train a policy offline, a fully scalable data-driven solution seems still far from reach. We have to think about novel approaches to tackle this problem. Reducing the problem space, pre-training and fine-tuning, efficient representation learning, large models for control, are all possible directions to explore.

Scalability of the control optimization will unlock the potential for large-scale energy savings, in which engineers , building maintainers, system integrators, and BMS vendors will all play a significant role. Specifically, “off-the-shelf” products being easier to adopt and integrate, their deployment will be faster and less costly, as they could be managed by the existing teams in charge of the building systems.